Nakata Taizou rummages through Japan's cultural attic

by Tim Young

From SIF SATELLITE 52, Winter 1998-99

also appeared in Eye-Ai,

February 1999

I

had a music teacher in college who said that, in terms of culture, "Japan

never throws anything away." That may be true, but it seems that a lot

of Japanese are unaware of a lot of what's stashed in the attic.

I

had a music teacher in college who said that, in terms of culture, "Japan

never throws anything away." That may be true, but it seems that a lot

of Japanese are unaware of a lot of what's stashed in the attic.

Take gagaku, for example, a musical form based on Chinese music that

has existed in Japan for at least 1400 years. I recently went to a large

department store in search of a gagaku CD. My initial search among the

traditional music CDs was fruitless, so I decided to ask one of the

shop clerks.

I approached a young woman in her early twenties, slightly chubby,

her hair dyed brown. When I asked her if they had any gagaku CDs, she

looked puzzled.

"Gagaku...," she repeated. I wasn't sure if she was just thinking,

or if she really didn't know what I was talking about.

"Old Japanese music," I added. Then the light went on in her face and

she knew which section to look in. (They didn't have any in stock, though;

I had to order one.)

To be fair, there aren't many people in any country who could tell

you anything at all about their local forms of music in the year 598.

The difference, however, is that, unlike most types of music from that

era, gagaku is still regularly performed; it has been called, "the oldest

continuous orchestral tradition in the world." And yet, there are Japanese

who don't even know what gagaku is.

"What is my native music?"

Nakata

Taizou used to count himself among this number. As a college student

in Osaka in the mid-1980s, he played in a rock band, and knew little

about the traditional music of his homeland. However, perhaps unusually,

this started to bother him.

"I was playing popular music," he says, "but one day I realized: I

was Japanese, but I didn't know Japanese instruments. Rock music is

native to America. I played rock. But I wondered, what is my native

music? So then, as I was looking for the answer to this question, I

discovered gagaku."

At age twenty, he quit university and moved to Tokyo to become a musician,

in spite of his parents' opposition to the idea. But his persistence

has paid off: he has learned to play the biwa and sho,

two gagaku instruments, and calls himself a "freelance gagaku musician."

Gagaku was traditionally played only within the Emperor's Court; before

the Meiji Restoration of 1868, commoners in Japan knew nothing of gagaku.

The Imperial Household gagaku troupe is still "the" gagaku troupe (the

CD I bought was recorded by them), but there are some, like Nakata,

who choose not join the Imperial Household. For one thing, it's very

restrictive: Imperial Household musicians cannot perform outside the

Imperial Troupe. Nakata's teacher is from the Imperial Household, and

Nakata could pass the test to join (which requires six or seven years

of study), but prefers to play at religious ceremonies, school demonstrations

of traditional instruments, and the like. (He spends the other half

of his time as a freelance computer software engineer; "It's impossible

to earn my living as a gagaku musician!" he smiles.)

Music for the Seasons

While demonstrating his instruments at schools, he met several other

musicians doing the same on other instruments. As a result, in early

1997 he formed a band, called T's Color, with koto player and vocalist

Hamane Yuka, bass kotoist Miyazaki Mieko, and Sakamoto Kazutaka on the

melodica, a keyboard instrument that is blown by the musician playing

it.

Along with the guitar, Nakata plays both of his gagaku instruments

in the band, but the band's repertoire is a far cry from gagaku; where

gagaku is ponderous and rather shrill, T's Color's music is made up

almost entirely of soft pop ballads. Their concert October 13 at Minami

Aoyama's Mandala live house consisted of gentle melodies, with layers

of beautiful, flowing koto playing. Before playing a tune called "Oyasumi"

("Good Night"), Nakata told the audience, "It's OK if you fall asleep!"

"We play pretty much quiet songs," he told me, "but we do have some

slightly more lively tunes." The liveliest one they played at Mandala

was "Harumachi Uta" ("Song of a Village in Spring"), a waltz-but, well,

a gentle waltz.

One of Nakata's compositions, Kiyose, is made up entirely of

seasonal words from haiku and tanka, he says. Naturally,

at the October concert, they played the "autumn version," - containing

such words as "hanano", a field of flowers, which Nakata says is an

autumn word from tanka - but there are different lyrics for the other

seasons. When asked if he often writes tanka or haiku, he's quick to

dispel that idea. "No, I don't!" he laughs. "Not especially. Just for

this song." Check the T's Color web site (http://www.zipangu.com/) for

further information.

One for the money, two for the sho

One

intriguing aspect of T's Color is that the melodica and sho have a similar

sound quality, both having a reedy, somewhat nasal sound. The sho reminds

me, in both sound and appearance, of a tiny pipe organ. The bamboo pipes

of different lengths, clustered together, look like they belong within

a tiny replica of a European-style cathedral. The sho is played by covering

tiny holes, one at the base of each pipe, while blowing into the mouthpiece.

Only the pipes whose holes are covered will make a sound, so many different

combinations of chords can be played. This is something which is hard

to do very quickly, but as the sho's function in gagaku is to simply

play the same chords for long periods, as a canvas on which the oboe-like

plainhichiriki paints its melody, dexterity is not something

for which sho players strive.

One

intriguing aspect of T's Color is that the melodica and sho have a similar

sound quality, both having a reedy, somewhat nasal sound. The sho reminds

me, in both sound and appearance, of a tiny pipe organ. The bamboo pipes

of different lengths, clustered together, look like they belong within

a tiny replica of a European-style cathedral. The sho is played by covering

tiny holes, one at the base of each pipe, while blowing into the mouthpiece.

Only the pipes whose holes are covered will make a sound, so many different

combinations of chords can be played. This is something which is hard

to do very quickly, but as the sho's function in gagaku is to simply

play the same chords for long periods, as a canvas on which the oboe-like

plainhichiriki paints its melody, dexterity is not something

for which sho players strive.

Nakata disassembled his sho to, well, show me how it worked.

Each piece of bamboo has a tiny reed, like a clarinet's reed, waxed

to it. The reed may be removed, "but only for maintenance. It's kind

of a pain to take it off," Nakata says.

"If the reed gets wet," he goes on, "it won't vibrate." This is a real

concern, because moisture condenses easily inside the pipes. For this

reason, sho players have long kept their instruments in pots atop charcoal

braziers, to keep the instrument dry. Nakata, however, uses a more convenient

electric sho warmer!

Nakata pointed out that the various versions of the sho around Asia

have different sounds and are played differently. "The Japanese sho

has a very clear sound, but the (Chinese) sheng is like a horn-like

a trumpet, like the theme from Rocky!" Also, he points out, while Japanese

sit still when playing the sho, "the Vietnamese sho is played while

dancing!"

According to Bragard and deHen (see sources), the sheng originated

in present-day Laos and Cambodia. Due to increased contact between Asia

and Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the sheng found

its way west, where it inspired Berlin instrument maker Buschmann in

1822 to develop both the mouth harmonica and the accordion. Less directly,

she sheng also brought about the invention of the concertina, invented

in England in 1844.

We got the lute

The biwa, too, has cousins in the West. The earliest lutes date back

to at least 1700 BC, in Babylon or Egypt. A 3-string lute, resembling

the Asian tanbur, is reported by Bragard and deHen as having

been known in Europe in the 800s AD. An Arabian instrument called the

oud evolved into the Chinese pipa, then the biwa, as it

moved east, and became the lute, and later the guitar, as it was passed

along through North Africa to Spain and the rest of Western Europe.

Compared to the oud, however, the biwa is not as versatile, and especially

not the kind of biwa used in gagaku. Nakata explains that the oud has

eight strings, while the biwa has only three. Also, unlike the oud,

the biwa has frets, and is much flatter than, say, the lute, whose back

is a half-pear shape.

While the oud and its Western progeny are made of thin pieces of wood

put together, a biwa is made by hollowing out a solid piece of wood,

and then covering the hollow area with a separate piece. Although it

is semi-hollow and rather thin, it is also surprisingly heavy. According

to Nakata, his biwa weighs 6.5kg, while a non-gagaku biwa weighs 5kg.

(The koto, a larger but more completely hollowed-out instrument, weighs

in at 5 kg.) Nakata's biwa has a mahogany back with a covering piece

made of a type of mulberry wood, but he says the type of wood used varies

depending on the craftsman making the instrument.

Nakata demonstrated the way the biwa should be played in gagaku, using

a bachi to pluck all three strings sharply, harshly, bringing

the bachi to rest against the cowskin covering. "In gagaku, the biwa

is a percussion instrument," Nakata points out. This seems clear from

my CD, where the biwa never carries the tune; instead, the three strings

are plucked at crucial points, in the same manner each time.

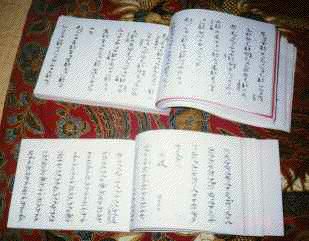

Nakata showed us his written music for the biwa and sho. However, he

points out (as does Togi; see sources) that written music in gagaku

is more like a memorandum than actual sheet music; "it is useless unless

the performer has a solid background of training in the use of the instrument

and has memorized the piece beforehand," Togi writes, going on to say

that "the professional performer is required to memorize the whole repertoire."

Beauty in simplicity

Hundreds of years ago, gagaku was more improvisational, with more complicated

parts being played, particularly on the biwa. However, since these parts

were passed along by imitation and never written down, they were eventually

lost, making gagaku more simple and minimalist. This may not have been

completely accidental, however, since Japanese culture has often found

more beauty in simplicity.

I showed Nakata my CD, and he said it had a good selection of gagaku

compositions. He went on to explain that the titles of the pieces show

which "key" the piece is played in, although this is not a "key" in

the Western musical sense; two different "scales" may start with the

same note, but follow with different notes. Each of gagaku's six keys

has special meaning; for example, the key called Oshikicho means summer,

the phoenix, the heart, and the color red. It also signifies south,

and other keys are associated with west, east, and north; therefore,

according to Nakata, the temple bells in southern Kyoto are tuned in

Oshikicho, with the bells in western, eastern, and northern Kyoto tuned

in the keys associated with those directions!

Besides the difference in key, it's hard for non-gagaku experts to

find much difference between one gagaku composition and the next. There

is a rather set pattern for each piece-the flute begins, then percussion.

The sho then comes in playing a chord, and finally the hichiriki begins

the melody, with accompaniment by biwa and koto.

Being a gagaku musician got Nakata a chance to play in a movie. The

film, "Kaze no Katami," was set in Japan's Heian Era (794-857 A.D.)

"It wasn't a very good movie," he recalls with a smile. "It was an interesting

book, but the screenplay wasn't so good."

Nakata's wife is also a musician, playing the koto. He laughs, "since

we got married, we never perform together!" They now live in western

Tokyo with their one-year-old son.

I asked Nakata how people react when he tells them what he does for

a living. "Most of them are surprised," he says. "Most Japanese don't

know much about gagaku. They're surprised that there are any people

who still play gagaku."

Sounds like it's time to do some rummaging in the attic.

Sources:

Gagaku: Court Music and Dance, by Masataro Togi. Introduction by William

P. Malm. Weatherhill, New York & Tokyo, 1971

Gagaku/Music Department, the Imperial Household. Nippon Columbia Co.,

Ltd. 1991.

Musical Instruments in Art and History, by Roger Bragard and Ferdinand

J. deHen. The Viking Press, New York, 1968.

Global Sounds home

![]() This page last updated

December 27, 2003

. E-mail Tim

This page last updated

December 27, 2003

. E-mail Tim